from Cinegraphic.net:

Walther Ruttmann's Lichtspiel Films

story © internetted, February 27, 2011 all rights reserved.

URL: https://www.cinegraphic.net/article.php?story=20110220082757118

An Excerpt from The History of Motion Graphics:

The term “absolute film” differentiates the fully abstract films produced in Germany from the related, also “abstract” films, produced in Paris such as Ballet Méchanique. Both groups of work are commonly grouped together as “Dada cinema.” This collection of films by Walther Ruttmann, Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling are the oldest fully abstract motion pictures still known to survive. While all lived in Germany and produced their films at around the same time, they did not constitute a “group” or movement. The first productions by Ruttmann date to the years following the end of World War I, during the lead up to the onset of the German hyperinflation following the collapse of the Reichsmark in July 1922.

Walther Ruttmann (1887 – 1941) was initially trained as an architect and painter; he served on the Eastern front during World War I, suffered “shell shock” (what is now known as post traumatic stress disorder), and on being released from the hospital abandoned painting to make films. As he was the son of a wealthy mercantilist, he had the financial means to become a film maker upon being released from the hospital, enabling him to work independently of UFA, the major German studio at the time. His first productions were abstract animated films, and were also the first fully animated cartoon work produced in Germany. Ruttmann’s titles for these works indicate their relationship to the synaesthetic heritage: Lichtspiel: Opus I was produced between 1919 and 1921. It premiered in April 1921, and was released for German theatrical distribution in 1922. It is the oldest fully abstract motion picture known to survive, using only animated geometric forms, arranged and shown without reference to any representational imagery; the first abstract films by Viking Eggeling and Hans Richter were not exhibited publically until 1923.

He followed it with Lichtspiel: Opus II, a second animation developing his visual ideas from Opus I, and refining the animation technique, but did not immediately move on to a third abstract film. The impact of the Weimar hyperinflation appears in the production gap between Opus II that premiered in April, 1922, and the his two final abstract films. During the period of hyperinflation he worked as an animator on commercial feature film projects for Fritz Lang, where he designed and filmed the dream sequence in Die Niebelingen (1924), and for Lotte Reininger’s film The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1924-1926), and the sequence called “Lebende Buddhas: Eine Phantasie aus dem Schneeland und Tibet” in a film directed by Paul Wegener (1924). He returned to making abstract films with Lichtspiel: Opus III produced from 1923-24, and Lichtspiel: Opus IIII, produced in 1925 as the German economy began to stabilize. Both premiered on May 3, 1925. This pattern of production interrupted by the 1922 period of hyperinflation appears in the work of Richter and Eggeling as well, but since they worked at the UFA studio, in a much less pronounced way.

Both Opus I and Opus II share a laborious paint-on-glass technique, employing oil smudges on plate glass, and supplemented by cut-out animations of angular forms. This technique is used to a lesser degree in Opus III, and Opus IIII was made using paper cutouts.

Lichtspiel: Opus I (1921) was composed with loop printing to lengthen and develop his motifs over its 12 minute duration. Composer Max Butting produced a score for Opus I that is closely synchronized to the action of the curves, triangles and bars that move around the screen. There are two sets of animated forms—one set are softly drawn, and their shape and movements are organic, the others are triangular, hard-edged shapes that jut into the screen, forcing the organic shapes to flee.

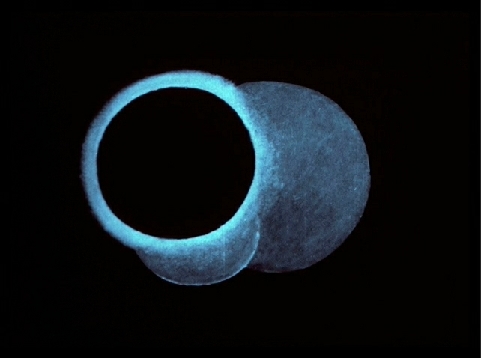

All of Ruttmann’s Lichtspiel films employ color to some degree. Opus I was the most complex in its use of color, with different sections being tinted or toned to give color to the animation, geometric shapes and the background, reflecting both the action and the mood, while breaking it into distinct movements that correspond to Butting’s score. The toned background follows the standard meaning for tinted film in the silent era, enabling the second movement, tinted blue, to be a nocturne.

Lichtspiel: Opus II (1922) expanded upon the formal innovations in Opus I, again employing a mixture of angular forms and organic forms done with the oil-on-glass technique. Although shorter, it is also faster paced, and clearly is a more developed version of the motifs and structure from his first film. However, it also included the use of kinestasis—still images animated through camera movement—and multiple planes of glass with animation, allowing two sets of curved animated forms, one white and the other black, to interact on screen, wrapping around and masking each other against a grey background. The animation is a mixture of curves, squares and rectangles, arrayed into compositions that reference the shape of the frame, which are all in motion at the same time. Different sections were toned different colors—blue, then later, red—the individual forms were not hand colored as in Opus I.

Lichtspiel: Opus III (1924) is composed from squares, rectangles and other straight-edged forms animated in overlapping, kinetic compositions. The shapes in this film are not solid colors, but graduated tones, and the development of each sequence is built around asymmetrical compositions that break the frame into harmonious sections. The result is dynamic, active: the moving shapes suggest the rapid movement of machinery, pistons. Then in the middle of the film there is a shift towards a bifurcation of the frame and oscillating patterns that rotate around this central axis, before a return to the asymmetry of the machine-like motions. The compositions employed in this film are unique in the 1920s, resembling the later work of Joseph Albers, or, the more contemporary work of Peter Halley in the 1980s.

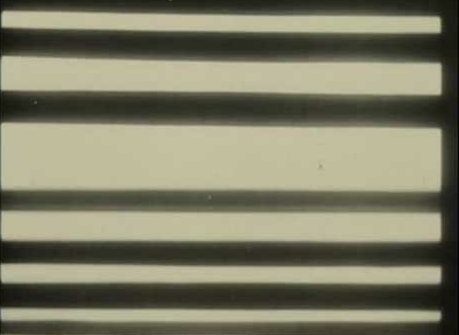

Color serves a dramatic purpose in this film. Short sections of red and blue alternate towards the end, creating a contrast, but as in Opus II, the whole frame is tinted, and there is no hand-painting. The alternation of monochromatic, colored compositions at the conclusion enables the end to achieve a dramatic resolution that was missing in his earlier films. This use of color for emphasis is repeated in his last abstract film, Lichtspiel: Opus IIII (1925): the first half the film is black and white, then it is tinted blue for a minute-long sequence of curved forms filling the frame, oscillating on screen, after which the opening black and white forms reappear, superimposed with the curved forms, then finally, the last two shots are bright red. The organization and imagery in this final film has even fewer parallels in the abstract painting of the 1920s. Composed in several sections, the first is made from bands of white and black that stretch horizontally across the screen, and “roll” between being white bands on black and black bands on white. These are interrupted by an ascending white blocks that moves outwards from the center, but does not empty the screen. Instead, these vertical bars move horizontally across the bands, creating graphic compositions. The closest parallel in film is Lines Horizontal or Lines Vertical by Evelyn Lambart and Norman McLaren in the 1960s; however, the imagery of Opus IIII resembles nothing else so much as the abstract video works of the 1970s by Gary Hill and the Vasulkas produced at the Experimental TV Center.

Lichtspiel: Opus IIII was the last fully abstract film Walter Ruttmann made; he would employ short abstract sequences in some of his other films: symmetrical abstract shapes like those in Opus III and Opus IIII appear as short graphic elements and transitions in Das Wiedergefundene Paradies (1925), Dort wo der Rhein (1927) and in the opening of Berlin, die Sinfonie der Großstadt (1927).

In considering all four of these abstract films in sequence, what emerges is a development away from the organic, soft-form animations of Opus I towards increasingly rectangular grid compositions and geometric forms. The adoption of a geometric abstraction demonstrates the shift towards non-referentiality and Constructivism that happens as the 1920s develop, a feature of abstract painting as much as abstract art: Kandinsky’s works of the 1920s also become progressively more geometric and planar as the decade progressed.

The influence of Ruttmann’s work on later abstract filmmakers comes primarily through the impact his work had on Oskar Fischinger who attended the first screening of Lichtspiel: Opus I in 1921. Fischinger would also begin making films during the 1920s, but did not produce fully abstract films until after optical sound was adopted as the standard in 1927. Prior to that he made a number of experimental animations using machines of his own design, including a wax-cutting animation device that Ruttmann bought, but apparently never used.