from Cinegraphic.net:

On Len Lye's Kinetic Film Theory

story © internetted, May 1, 2011 all rights reserved.

URL: https://www.cinegraphic.net/article.php?story=20110430082518916

Len Lye (1901 – 1980) worked as an animator, then as a director of newsreels for the March of Time from 1946 to 51, and finally as a kinetic artist; within the history of motion graphics he occupies an unusual position: even though he had informal training as a painter and worked with various types of sound-image synchronization in abstract film, these works exhibit a distinct conception of abstraction as a kinetic art, rather than an art constructed upon a musical analogy as was typical for the other artists drawn to create abstract motion pictures during the first phase of their history. This emphasis appears in his theorizing shortly after his first hand painted film had achieved a wide-spread critical success in Europe. Writing with a collaborator, Laura Riding, in 1935 for the essay “Film-making,” Lye proposes a tentative framework to think about motion as form:

1. Form in movement-compositions is the total effect of accidental design created by cross-movements, perspective movements, timing, accenting—all the varieties of action whether in natural juxtaposition or not.

2. There is a possibility of isolating a movement-consciousness by reverting to such reflex-spontaneities as hereditary instincts are composed of. It might even be said, perhaps, that this gift of physical immediacy, which is the gift of a consciousness of movement, is discoverable through the brain in blood, organs, tissues, nerves: that a physical time-sense can be physiologically cultivated.

3. Consciousness of movement may be purely receptive, as a passive sensing of the vibration-pattern: so we might speak of a sense of movement just as we speak of a sense of telepathy, meaning a receptive intuition of other people’s thoughts, or a theosophic sense, meaning a receptive intuition of things unknown.

The proposal being made in these three axiomatic propositions is that motion and movement are autonomous sensory phenomena based in our ability to recognize the passage of time (time and movement are equivalent here), and our perceptions of movement happens as a recognition of something present in the world around us, but at the same time absent in itself: movement only become apparent through the pattern of its action—where it has been and where it goes as we watch. This understanding of the apparent motion of film is fundamentally perceptual, a construct that necessarily combines the perception of movement with the recognition of duration. However, even as movement is a natural component of the physical world, the concern Lye has is with its perception:

4. Or we might say, speaking in terms of light, colour, sound, atoms, that nothing physical exists in a static state. But at the same time, we should have to say that by movement we meant not external or mechanical movement, but movement as our own physical existence projected outside the mind and seen as living. And further, that when the mind is movement-conscious it is conscious of nothing else: in fact, is something that precedes what is strictly called consciousness, as physical precedes mental.

The ability to see something move does not depend on a conscious decision by the viewer, it is an innate, autonomous process outside of conscious control—yet, in a startling recognition, Lye’s theory understands movement as an internal interpretation of the viewing mind that is then assigned to perceived external stimuli. The recognition of movement, however innate, is a construction reflecting some mental activity.

Lye concludes this set of axiomatic proposals with a comment about the role of film—motion pictures—in relation to the distinctly perceptual-kinetic framework he has proposed. These foundations, considered in relation to his film work, leads towards the creation of works that converge with the audio-visual concerns of visual music:

6. Film is technically the best method for the isolation of visual movement. As sound and visual movement are equal in timing they can be balances with accents and silences in film.

However, his concern with movement is a qualitative distinction that separates Lye’s films from those of other artists active in the 1930s. The relationships between the visual forms and the soundtrack that are produced by his films move between organization around specific note-form (as in Oskar Fischinger's films) to the counterpoint relations of form to soloist performance, and the rhythmic break up of the film into sequences corresponding less to specific parts of the music than to the mood or tone of a sequence. This difference probably originates with his background, unique among artists of this period: an autodidact, he learned the forms and approaches of Modernism at one remove, via books and magazines at the library in Christchurch, New Zealand—a location distant from the conversations, arguments and debates shaping the emergent abstraction at the start of the twentieth century. Instead of developing his ideas of abstract form within the cultural horizons of the European avant-garde (and its relatives in America), Lye developed autonomously: thus, where music provides the aesthetic reference point for the synaesthetic abstraction developing in the Euro-American tradition of abstract film, Lye’s aesthetic begins with a concern with motion—the idea of a kinetic art that he would develop graphically with the apparent movement of cinema, then later employing the eminent movement of motorized, kinetic sculpture.

However, the conceptual basis of his work as kinetic, (vs. the more common musical analogy), does have parallels to musical form. Joseph Schillinger noted the relationship between movement and music in his 1937 discussion of music, “The Destiny of Tonal Art.” The recognition that movement is a foundational principle of reality informs both Schillinger and Lye’s conceptions of motion as central to the organization and development of musical arts; the distinction between them lies with how that idea informs and develops in their otherwise independent aesthetic systems. A concern with motion does not preclude interest in or concern with a music-like organization for a film.

While his work develops from an aesthetic of movement attached to specific forms—his “figures of motion”—Lye’s work in both film and kinetic sculpture lie along twin, successive trajectories, each with their own distinct audiences and particular histories that do not generally overlap. Roger Horrocks, Lye’s former assistant-turned historian, explains the connection between this conception of movement and Lye’s films:

The term ‘figure of motion’ had the advantage of being applicable to films, kinetic sculptures, or any movement in nature. Familiar examples included a wave rolling in and breaking, or a graceful ‘figure skater’ making patterns on the ice. One of Lye’s favorite examples was a child waving fireworks on Guy Fawkes Night: “When a . . . sparkler described a figure eight, the persistence of after-image isolates its motion as design.” Lye was, however, less interested in the ‘after-image’ than in the pattern-making implied by the word “describes.”

It is this element of form created by a specific, particular movement spread over time that defines the concept of “figure of motion.” Thus, what is of concern to Lye as a theorist is not the perceptual form created in optical perception, but the visibility of motion that optical trace enables. This distinction is significant for how this aesthetic develops its forms and the ways in which those forms are put into motion.

Lye’s work as a film maker proceeded through a combination of experimentation on his own projects combined with practical on-the-job training working at film production companies that specialized in creating animated films. His first completed film, produced in London over a two year period, Tusalava (1929) was done using standard animation techniques: individual hand-drawn artwork was photographed on an animation stand during his off hours at work. The Samoan title, translated by Lye as “Everything eventually goes full circle” employed vaguely Surrealist, primitive drawings related to the work of Hans Arp.

A Colour Box (1935) produced during 1934, proceeded from an entirely different basis than his first attempt; it is the oldest surviving hand-drawn motion picture. (At the time of its production, earlier work by the Futurists was essentially unknown, and Mary Hallock-Greenewalt’s experimental hand-painted “films” were only playable on an idiosyncratic device of her own design, and were not “motion pictures” except in a generic sense that they moved intermittently.) This basis made A Colour Box a topic of much discussion, and it screened widely in Europe, eventually winning a Medal of Honor at the 1935 International Cinema Festival in Brussels.

A Colour Box was Lye’s first project done under the sponsorship of John Grierson and the GPO Film Unit. This organization was a division within the United Kingdom’s General Post Office, begun in 1933 as a reorganization of the earlier Empire Marketing Board Film Unit that was responsible for creating advertizing films for the government. Under John Grierson, the GPO would become an instrumental organization in the development and production of socially-engaged documentary films. Lye’s first work with them was created to be shown in color in a program of black and white films; after its initial success, Grierson would commission four more animated films from Lye—one per year—with the only requirement imposed on A Colour Box that it end with a message advertizing postage for the post office. Ultimately Lye would only produce 3 animated films for the GPO; the fourth was the live-action film N or NW about the dangers of misaddressing a letter.

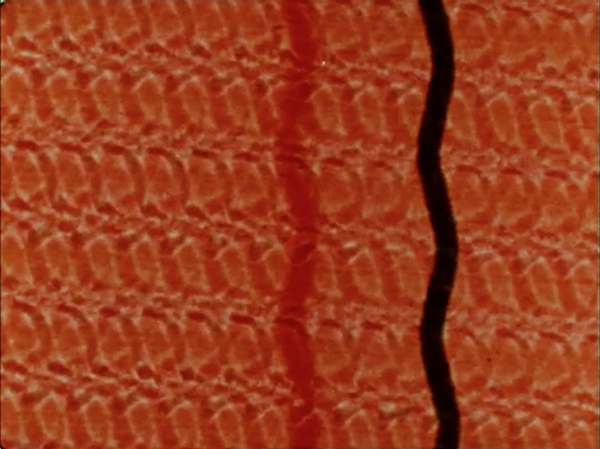

His rediscovery of hand-painted (direct animation) film became the foundation of the animation techniques Lye would develop over the remainder of his career making abstract films. However, his production of hand-painted films was not entirely limited to working with direct-on-celluloid techniques: A Colour Box used a series of title cards for the opening credits, over which he applied his painting, using a combination of stencils to create repeating shapes across the strip without concern for the individual frames, and scrapers to “cut” lines into the wet paint before it dried. The subtractive process introduces the common element that reappears in almost all Lye’s films: a ‘figure of motion’ in the form of a vertical line that modulates in response to the music. These different graphic elements are roughly synchronized to the music—different elements are on screen at the same time as different instruments take up solos. This linear form runs throughout A Colour Box; it appears across Lye’s entire body of work, visible both in his films and in his kinetic sculptures. His next film, produced as a tobacco advertisement, would refine these stencil and subtractive techniques further.

Len Lye’s Kaleidoscope (1935) was sponsored by the Imperial Tobacco Company, and featured music by Don Bareto and His Cuban Orchestra. Following the design of his earlier film, Lye shot the titles using an animation stand, but painted color fields and wipes over them, integrating the traditional animation into the hand-painted. Kaleidoscope presents improvements and shows a clear development of his stenciling technique: where graphic patterns dance without great concern for the individual frames of A Colour Box, this second film incorporates carefully registered stencil animations of spinning disks, star shapes, and subtractively, dancing rectangles that represent cigarettes. Further unlike his GPO film, the animation is not simply an abstraction with advertising message at the end—the films nature as an advertisement structures and organized the imagery throughout. The spinning disks recall cigarette labels, the stars suggesting the burning coals of the lit cigarettes themselves.

As with both Oskar Fischinger in Germany, and Mary Ellen Bute in America, Lye worked with familiar, popular music. The choice to employ Cuban music reflects a mid-1930s European fad for Cuban performers of various types—both dancers, singers and bands. The combination of abstract animation and popular music is a common feature of pre-World War II abstraction generally once the sound film and optical sound track replaced the live performers of the silent era.

Rainbow Dance (1936) was Lye’s second GPO Film Unit sponsored production. As with his first GPO film, this one also ended with a message from the post office: “The P.O.S.B. puts a pot of gold at the end of the Rainbow.” Unlike his first production where the relationship between the advertizing message and the rest of the film is uncertain, in Rainbow Dance their connection is obvious, if also literal. He employed a new type of color film that Oskar Fischinger had also used to make his color films starting in 1932. The Gasparcolor film created a full color image from three black and white color separation negatives that would be printed together to produce a single finished print. In making Rainbow Dance Lye employed both live actors with sets and hand painted elements that were combined in the printing process; his use of this film stock was fundamentally different from how this stock would normally be used. The colors that appear in the finished film result from how Gasparcolor employed separations: each element of film was produced from a black and white original—no color was used in the sets or graphic elements in the film. Lye discussed this process at length in his essay “Experiment in Colour.” It developed a different approach to the creation of color:

The difference in colour technique for this film as compared with the shooting of a straight colour film is that all colour records were taken as separate films. No colour was used in the sets, where every object was painted in terms of black and white. For instance, a green hill (a ‘prop’ hill) was painted white and photographed continuously for the red record, painted dark grey and photographed for the yellow record, painted a light grey and finally photographed for the blue record. This meant the fill was split into three records for the required densities of the pink, yellow and blue dyes of the Gasparcolor film stock.

The creation of color via the printing process meant that the final color effects of the film would have a translucence and brilliance unrelated to the actual colors of the material filmed, while at the same time breaking the visuals on screen into a spectrum of hues—the “rainbow” described by the film’s title. It has the effect of separating the colors shown from the forms seen on screen—as different moving elements overlap, their colors interact and combine independently of their shape or motion. This exploration of the physical potentials of color in film would lead to his final animated film done at the GPO, one that developed the combination of live and animated elements, as well as the orchestration of color in a laborious production process that anticipates commercial motion graphics produced in the 1980s and 1990s that employ video and computer graphics.

Lye’s continued involvement with the GPO allowed him the opportunity to further develop his techniques combining filmed material with direct, hand-painted animation. The results of these experiments are visible in Trade Tattoo (1937), a documentary of “the rhythm of work-a-day Britain” that was made with outtakes from other GPO films which were carefully combined with hand-animated elements. As in all Lye’s hand-painted films, the synchronization of sound to animated forms becomes increasingly acute, partly an effect of montage, where as instruments change, there is a cut to a new piece of animation. The difference between this film and his earlier ones, however, is immediately apparent in the “Fires are lit” sequence where a mixture of hand-drawn words, representational animation of flames, Lye’s familiar animated dots, and extremely high contrast footage—rendering only black and white with limited grey scale—of a smelting furnace pouring out molten metal. The dots, flames and lines in the animation dance, while the live action footage follows the music in a rhythmic montage. This combination highly abstracted, yet still recognizable live action with highly synchronized animation is an extension of the potentials present in Lye’s first direct film, but also a movement towards the highly synchronized animation employed by Oskar Fischinger at the start of the decade. This shift towards closer audio-visual relations and easily recognizable subject matter may be the impact of audiences hostile to highly abstract art, a constant issue present since the first abstract films were commercially distributed in the 1920s.

When John Grierson left the GPO in 1938 to set up the National Film Board of Canada, Lye lost his primary supporter at the GPO, ending his involvement with the organization. He would continue making direct animations, producing three more before World War II as advertizing. The first, Colour Flight (1938), was made for Imperial Airways (later renamed British Airways) where the visuals were built around an animation of the company logo. Swinging the Lambeth Walk (1939) was made for TIDA, the Travel and Industrial Development Association, and Musical Poster #1 (1940). In 1941, Lye joined the Realist Film Unit and began making propaganda films for the Ministry of Information where he made six live action documentaries. This work lead to a job with an American newsreel series The March of Time from 1944 to 1951 when the newsreel ended production—enabling him to travel to New York during World War II, where he would remain for the rest of his career.

While living in New York he only made a few films on his own. He collaborated on film projects with the younger film makers: Lye added the color effects to Ian Hugo’s The Bells of Atlantis (1952), a film adaptation of his wife, Anaïs Nin’s poem of the same name. Lye’s own work during this period is limited. Color Cry (1953) employs many of the familiar direct animation techniques developed in the 1930s, but because it has a soundtrack performed on harmonica by Sonny Terry, the animated forms have a dramatically different character: while synchronized to the vocals and harmonica, their impact is less one of a visualization of sound than a counterpoint to that sound. The shifting relationship between the visuals and the soundtrack is a feature of Lye’s later scratch films as well.

Yet, in spite of his involvement in the New York art scene following his arrival in 1944, and continuing throughout the 1950s, (he was a regular at the Cedar Tavern and “The Club” where the Abstract Expressionist painters—Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem DeKooning, et. al—gathered), Lye’s films during this period were never linked to the broader concerns of action painting, even though the language Harold Rosenberg developed to discuss this type of new American painting apply equally well to Lye’s work. Instead, Lye’s theorization anticipates and follows other avant-garde developments outside of motion pictures or painting. In his essay “Is Film Art?” (1958) he ultimately declares he will “go on strike” and not make any more films without institutional support. In this essay he considers the relationship between the New York School’s development of action painting and his own film work, noting about the relationship between movement, stillness and perception in a description that is distinct from the concerns with painterly surface, gesture and the traces of movement common to discussions of Abstract Expressionism:

The increasingly pronounced kinetic quality of 20th Century art evokes a sensory rather than an intellectual involvement. It would seem that the sensation of being—of actually existing—can become an underlying involvement with the imagery of art without a work literally depicting aspects of everyday realism. ‘Action Painting’ is a notable U.S. contribution to art.

We infer the supreme orienting power of bodily kinetic sensation when we say we must pinch ourselves to see if we are awake.

Some of our activities have been cultivated purely for kinesthetic enjoyment, such as dancing and sports. It follows that immobility, stillness, quietude have a contrapuntal effect on our sense of motion as silence emphasizes sound.

The opposition Lye proposes of motion vs. stillness, on a parallel to the idea of silence vs. sound, evokes the musical theorizations of composer John Cage who arrived at a similar reduction in his late compositions: the rendering of silence as a counterpoint to the creation of sound. This theory brings his last film works specifically into a musical context, but on strictly visual terms.

Free Radicals (1958) was produced as a result of an invitation by the International Experimental Film Competition at the 1958 Brussels World Fair in Belgium; it won the second prize at the festival, an award that included $5,000 in prize money. Unlike all of Lye’s earlier direct animation films, Free Radicals was not hand painted; instead it was an adaptation of his subtractive painting process, done on optically black leader where the only imagery visible on screen is a result of his scratching away the black emulsion. In an interview with Gretchen Berg for the magazine Film Culture, Lye explained his scratch process:

I made Free Radicals from 16mm black film leader, which you can get from DuPont. I took a graver, various kinds of needles. (My range included Indian arrowheads for romanticism.) You stick down the sides with scotch tape and get to work with scratching the stuff out. You spit on or dampen the celluloid with a sponge. Now the question is register. You’ve got sprocket holes to guide you. When you hold the needle, you dig it in through the black emulsion into the film and then start doing kinds of pictographic signatures. You hold your hand at the right height and act as if you were making your signature.

The on screen result of this process is a transformation of his forms from lines and colors into pure white shapes set against a completely black field, but the visual language remains the same as in his earlier film work: Lye’s common motif of vertical lines dancing to the music appears throughout this film, at times apparently rotating in space, while graphic patterns and dots provide accompaniment. The closely synchronized to the drum and vocal music by the Bagrimi Tribe, the abstract forms simultaneously suggest a physical landscape of waving grass and distant hills or mountains. This was the last film Lye would produce without outside support and funding, resulting in his shift from film making to kinetic sculpture. The central motif of his film work—the vertical line and its organization in groups—appears in his kinetic sculptures, demonstrating his shift to a new medium did not involve a break with the concerns of his earlier film work.

Lye’s last films, Particles in Space (1979) and Tal Fallow (1980), both developed from short experiments and studies produced in the 1950s and 1960s using the same technique as Free Radicals. They were completed with the assistance of the United States National Endowment for the Arts and the New Zealand Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council. Both explore the visual potentials of scratched imagery discovered in Free Radicals and are closely synchronized to their musical scores. In many respects these final films were analogous to his 1930s direct animation films where the potential to combine hand painted elements with live action provided the aesthetic “space” for his explorations, moving towards a logical elaboration of the potentials of his invented technique.