from Cinegraphic.net:

"Beyond Spatial Montage" part 3 of 6

story © internetted, November 15, 2014 all rights reserved.

URL: https://www.cinegraphic.net/article.php?story=20141104074914587

This theory work will be published as a book-length monograph Beyond Spatial Montage: Windowing, or, the Cinematic Displacement of Time, Motion, and Space by Focal Press.

Part 3 of a 6 Part series proposing an expanded theorization of spatial montage, excerpted from a current book project.

Time—Motion Displacement (Step Printing)

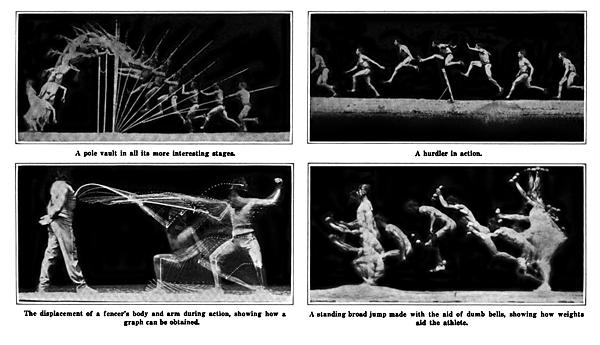

Time—Motion displacement is part of the foundational history of motion pictures. This type of sequential photograph, the chronophotograph, invented by the French scientist Etienne-Jules Marey, is immediately recognizable as representing a temporal shift where an identical, multiple-yet-singular formal structure of displacement is created entirely within a singular full-frame image. This displacement achieves a distinct juxtaposition and fragmentation of time and motion that is different in character and degree from ‘spatial montage’—the spatial element extending across the screen, is incidental to the organization as it is motion that characterizes these repetitions. This displacement of the duration across the screen as the individual motion ‘echoes’ violates the continuous long take in precisely the same way that editing and other forms of montage do, but without breaching the integrity of the individual shot. Superimpositions produced with an optical printer (or using video/digital processing) can produce a visual displacement called “step printing” that transforms the chronophotograph into a motion picture.

Georges Demeny, studies of human motion from “The Human Body in Action,” Scientific American, February 7, 1914.

Step printing employs a single take as the foundation for a new image, one where the motion contained in the individual frames of that original shot is presented simultaneously on screen, producing visual effects similar to those shown in the Demeny photographs (above). The image is made by repeating the same footage in a superimposition, but using an incremental advancement between repetitions; this the “step” in ‘step printing.’ It transforms the already filmed action of a shot into raw material for new animation where the initial imagery is juxtaposed with its own path of action and development. The emphasis in shots of this type is on the development and progression of action as extended over time across the screen. The spatial element of Time—Motion Displacement, while inherently a part of the work, is insignificant; the image on screen remains singular. The affect of these ‘echoes’ is immediately understood to be both simultaneous and indicative of multiple images coexisting on screen at the same moment—the tendency to interpret this kind of image as indicative of ‘the infinite’ suggests an understanding of the images shown as multiple-yet-singular.

Ways to automate of the step-printing effect have found few direct applications in commercial film and video production until the 1970s, but are abundantly common in Video art. The repeating imagery characteristic of video feedback displaces its form within the frame, but repeats that form with a varying degree of immediacy, a reflection of the latencies contained by the technology, ranging from instantly to after a tiny delay. The closed-circuit loop of camera watching its own output creates mandala-like forms from the repetition of the phosphor dots in the video screen—an element that may be a factor in its rapid adoption and deployment during the “psychedelic era.” It is a readily accessible technique for processing imagery using the video camera. Video feedback that integrates imagery, (rather than the autonomously generated visuals produced by a camera-monitor loop whose images emerge ‘purely’ from the interaction of pixel and camera), will also produce a similar series of Time—Motion displacements.

A similar relationship appears with the visual repetitions characteristic of some types of digital glitch (such as datamoshing) that produce another variation on the form of these Time—Space displacements. These repetitions however, do not have the affect of hyper-fast motion that exceeds the standard frames-per-second speed of film or video. These bits that remain in place imply a Cubist-like composition of shards, each showing a discrete moment in the development of the image—motion transformed into graphics. The difference between fragmented time and fragmented space lies with the overall composition of the materials combined on screen.

The digital imagery generated by this process is broken into discrete blocks that repeat across the screen, visual traces created by the parts of the image in motion across the spaces where there is no movement. This ‘dragging’ of form behind the leading edge of the motion element recalls the same chronophotographic repetitions appearing in Marey’s works—it is a technological artifact that not only has the same visual affect, but is representational image of how the motion was digital encoded in the file: as a discrete sequence of unique positions in motion over time; normally invisible, the changes to the video files’ data makes this fragmentation visible. Time is displaced spatially within the image.

Beyond Spatial Montage:

Part 1 Foundations

Part 2 Time—Space Displacement

Part 3 Time—Motion Displacement (Step Printing)

Part 4 Motion—Space Displacement (Mirroring)

Part 5 Time—Motion—Space Displacement

Part 6 Afterword