|

Marcel Duchamp (1887 1968) produced only one film, Anémic Cinéma (1926). It shares some of the concerns with creating an abstract visual language, but stands apart from the translation of the implied movement shown in abstract painting to the apparent motion of cinema. This film, shot by Man Ray, creates a visual comparison between a series of risqué French puns and a number of kinetic optical illusions that oscillate between convex and concave when spun. The relationship between the visual and verbal elements of this film is intricate; the complexity of meaning contained by this formulation is belied by the simplicity of the film itself. Understanding it requires a consideration of how this film and its subjects can be related to the rest of Duchamps oeuvre. This process reveals the abstract language Duchamp proposed in this film and his other works.

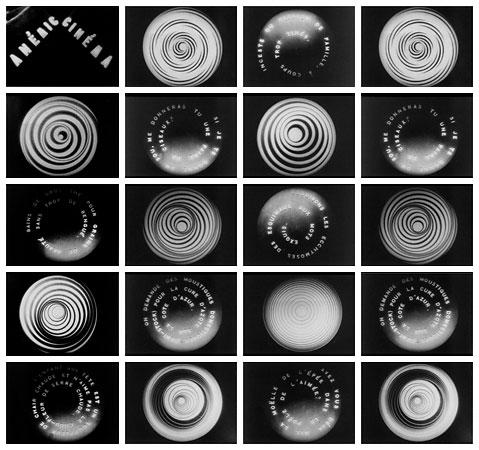

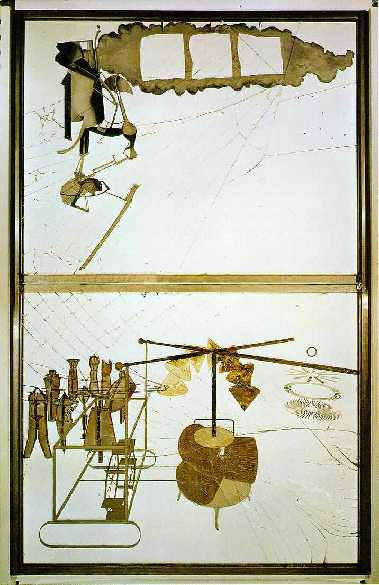

The oscillating disks so obviously on view in Anémic Cinéma are what Duchamp called precision optics; his name for the specific illusions used in the film was rotoreliefs. These early examples of kinetic art were originally designed for exhibition on the spinning turntable of a phonograph. Once set in motion, they visually pulse between positive and negative space. Duchamp has identified this apparent movement as cinematic blossoming; he directly connects it, so literally visible in Anémic Cinéma, with the role of desire in his painting-on-glass, The Large Glass (1915-23). This note from his publication The Green Box documents his process in the design and uncompletion of the painting:

The bride basically is a motor.

The whole graphic significance is for this cinematic blossoming. This cinematic blossoming is by the electrical stripping (see the passage of the bach. machine to the bride)

The last state of this nude bride before the orgasm which may (might) bring about her fall graphically, the need to express in a completely different way from the rest of the painting, this blossoming.

[Marcel Duchamp. The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Michael Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1989), pp. 42-43.]

The blossoming cannot be presented; what the depicted machinery in this painting does cannot be shown. Yet, the completely different way he mentions can be recognized as a demand for actual motionmaking his use of the cinema, and the appearance of the rotoreliefs (with their blossoming action) not coincidental. The connection of the rotoreliefs to The Large Glass is appropriate if only because the pulsating movement so visibly resembles blossoming, but at the same time is an effect beyond the ability of painting to produce: without movement, there is no illusion in the rotoreliefs.

The Large Glass as installed at the Philadephila Museum of Art.

Yet, the verbal elements are essential to interpreting the significance of the rotoreliefs: the apparent sexual meaning of the film comes not from the puns or the optical disks, but from their interaction. However, the puns composed and put in motion by Duchamp are difficult to translate because, as Film historian P. Adams Sitney explains:

Something else happens when we begin to allow the puns to have their play. The figurative meaning of la moelle de lépée and la poele de laimée over powers the literal (non)sense. The reference to sexual intercourse could hardly be more evident. Furthermore, once we recognize its figurative character, our reading of the other disks begins to reveal sexual allusions.

Suddenly the abstract gyrating shapes which rise from and sink into the plane of the screen come to resemble the igloos, breasts, welts and genitalia evoked by the words. The sexuality is neither in the literal meaning of the words, nor represented in the optical illusions, seen by themselves.

[P. AdamsSitney, Modernist Montage, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), p. 25.]

Sitney recognized that sexuality is the subtext to this film, but it is a subtext which requires the interpretation of the viewer looking at the juxtaposition of rotorelief and the text. However, as Katrina Martin has noted in her essay on the problems with translating the text in Anémic Cinéma, these statements are untranslatable; Duchamps statements are built from alliteration and puns that are a fundamental reflection of the differences between spoken and written Frenchsimply translating them to their English equivalent necessarily loses the word play that is so important to their affect, effectively denuding this use of language of its peculiar quality. The sexual interpretation of Duchamps puns are an overlay from verbal to visual, applied to the image; the puns, in order, are:

Bains de gros thé pour grains de beauté sans trop de bengué.

Lenfant qui tète est un souffleur de chair chaude et naime pas le chou-fleur de serre-chaude.

Si je te donne un sou me donneras-tu une paire de ciseaux?

On demande des moustiques domestiques (demi-stock) pour la cure dazote sur la côte dazur.

Inceste ou passion a coups trop de famille, à coups trop tirés.

Esquivons les ecchymoses des Esquimaux aux mots exquis.

Avez-vous déjà mis la moëlle de lépée dans le poêle de laimée?

Parmi nos articles de quinquillerie par essence, nous recommandans le robinet qui sarrête de couloir quand on ne lecoute pas.

Laspirant habite Javel et moi j'avais l'habite en spirale.

These word plays act through a double meaning which becomes apparent to French speakers, even though the statements are nonsense, when read aloud. The structure of these statements depends on the sound than the (normal) referential meaning. The precise nature of this verbal nonsense is essential to the construction and meaning in Duchamps film. Sitney further explains this organization:

At first sight Anémic Cinéma would seem to underline the difference between optical and verbal images. The two modes of representation are held together by the figure of the spiral. Yet we automatically apprehend them differently. The eye grasps the eccentric circles as if they were geometrical wholes.

While the view sees one set of disks as creating depth, he reads the other set as flat because of his reflex to the familiar orthography of the Latin alphabet. Thus, the viewer is the victim of an automatic response at odds with the ontological sameness of the shots.

[P. Adams Sitney, Modernist Montage, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), p. 24-25.]

Duchamp used the rotoreliefs as half of the visual material in Anémic Cinéma, the French puns were also placed on a spinning disk, the text arranged in spiral that moves from the outer edge towards the center. If we also recognize that as with a record, the rotoreliefs have a hole in the center which is registered on a pin centered on the turntable, the mounting of the disk recalls the sexual metaphor which is repeated throughout the iconography of this film.

film stills from Anémic Cinéma.

The doubling of the puns parallels the doubling of the rotoreliefs. The gyrating shapes movement originates in the inconsistency of human perception which optical illusions exploit. It is the interpretative shift of the precision optics which moves the experience of looking from the purely visual into the mental realm. The rotoreliefs and their use in Anémic Cinéma recall Duchamps famous claim that:

Painting should not be exclusively visual or retinal. It must interest the gray matter; our appetite for intellectualization.

[Cleve Gray, The Great Spectator interview, Art in America, (July-August, 1969), vol. 57, no. 4, p. 21.]

The objection Duchamp has to retinal art does not lie with the optical experience, but with the issue of mental engagement in what that visual experience signifies; this bias suggests an art where the semiotic organization of visual elements is the focus. The optical component of this film is an illusion: what we see in looking is different than what the rotorelief is physically. While the retinal effect of the texts and rotoreliefs in Anémic Cinéma have a different perceptual character, their meaning is en effect of our interpretationa result of intellectualization.

Sitney is correct that the sexuality is neither in the literal meaning of the words, nor represented in the optical illusions, seen by themselves, the semiotic conversion of a retinal impression in Anémic Cinéma into sexuality is connected to the system of construction Duchamp presented in The Green Box (1914). His system creates a linguistic formalism derived from the abstract system of mathematics. It allows his introduction of a formal component into the work provided that the viewer is aware of the system he employs:

Conditions of a language:

The search for prime words (divisible only by themselves and by unity).

Take a Larousse dict. and copy all the so-called abstract words. i.e., those which have no concrete reference

Compose a schematic sign designating each of these words. (this sign can be composed with the standard stops)

These signs must be thought of as the letters of the new alphabet.

[Marcel Duchamp, The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Michael Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1989), p. 31.]

The invention of new signs for an abstract language corresponding to terms in a dictionary without concrete reference divests language of its meaning, allowing its manipulation in purely technical terms. The function of the puns and word-play of this film can be recognized in his system of prime words. Each pun replays the action of the rotoreliefs linguistically, translating them from language to visual form. Yet for the translation of terms to be comprehensible requires an awareness of the systems of substitution for them to become legible. Alternation in the sequence of the film demonstrates their interchangeability. This transformation of abstraction into a complex web of meaning based upon an internal set of referentsthe other works by Marcel Duchampthe equivalences involved in the movement of oscillating visuals and punning text, instead of simply being a juxtaposition of neutral content, is logical within Duchamps system; it is evidence of the semiotic organization of his material. The formal system Duchamp devised is representational; the meaning of the rotoreliefs, while apparently works of pure abstraction comparable to those of Ruttmann, Richter or Eggeling, nevertheless have a specific meaning, thus the sexual context transforms how we understand these figures, shifting them from the realm of pure abstraction to something more closely related to the sublimation and substitution common to the works of Surrealism.

The Large Glass

It is a transfer that renders the work difficult, opaque to easy examinations. Art historian Anne dHarnoncourt explains the problem with looking at another of Duchamps difficult works:

The Large Glass and some of its studies are, of all Duchamps creations, the most accessible (to the point of being literally transparent) as well as the most abstruse. We see through them more than we see them. The viewer becomes part of the view.

[Anne dHarnoncourt and Walter Hopps. Etant Donnés

: 1 la chute deau, 2 le gaz declairage: Reflections on a New Work by Marcel Duchamp, second reprint of the Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin, volume LXIV, numbers 299 and 300, April-September, 1969, with the 1973 afterword by Anne dHarnoncourt (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum, 1987), pp. 8-10.]

Her description of The Large Glass could easily be a description of Anémic Cinéma as well. The difficulty of this film lies with ways the transparency of the work is also its opacity: what we see and what it means are separated by a gap which must be filled with careful attention to the details not of the work immediately before us, but its relationship to prior knowledge of Duchamps other works. This complex relationship appears in the title Anémic Cinéma which is a near-palindrome, almost spelled the same forwards as backwards. There is a self-similarity in the organization not only of his film, but of his other creations.

Duchamps attempt to create such a language of visual form unites his film with in the development of all the early abstract films; the differences between his work and that of other artists lies with how he worked to create his abstract language, a matter of technique rather than goal. The role of language, both verbal and visual, in the construction of motion graphics is one of the essential concerns of the field as it develops. Duchamps film can be recognized, as with Ballet Mécanique, as a tangential development, offering a glimpse of an alternate way the integration of text and image could have developed. But at the same time, his use of cinema as a medium for the construction of a semiotic system where the visual achieves a linguistic function should not be discounted. The transformation of graphic element to meaning bearing sign is the essential feature required for the development of a visual language. Duchamps work is especially notable in the history of motion graphics because it achieves this transfer so effectively, communicating a complex meaning that is not present in either his optical disks, the spiral texts, or their juxtaposition alone: it emerges from the relationship they also have with the rest of his work.

|

|